Gender Norms and Social Norms: Differences, Similarities and Why They Matter in Prevention Science

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (Cislaghi); Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University (Heise)

"Greater intervention effectiveness might come from increasing practitioners' clarity of the differences between social norms and gender norms."

Many of the practices being addressed in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), such as female genital cutting, child marriage, and intimate partner violence, are highly gendered. As a result, the stream of work on social norms has begun to intersect with earlier efforts to address gender norms. Yet these two traditions advance very different conceptualisations and understandings of norms and how they operate. This article examines similarities and differences between social and gender norms and discusses what each field can bring to social improvement efforts.

Traceable in thinking as early as Aristotle, Hume, and Locke, social norms are rules of action shared by people in a given society or group; they define what is considered normal and acceptable behaviour for the members of that group. Three key features of social norms theory include:

- Interventions using a social norms approach often leverage the misalignment between (i) people's individual behaviours and attitudes, and (ii) descriptive and injunctive norms (people's perceptions of others' behaviours and attitudes).

- Various streams in social norms theory posit that norms apply within a "reference group"; that is, different groups of people have different rules.

- Interventions explicitly based on norms theory have tended to focus on interdependent actions, which require coordination between individuals to achieve one's goal.

While "gender" as a term was popularised in the 1970s by feminists, gender norms first entered the health and development lexicon in the last decade of the 20th century, when several international bodies were making a global commitment to promote gender equality. Norms are but one element of the gender system, along with gender roles, gender socialisation, and gendered power relations. In this account, gender norms are the social rules and expectations that keep the gender system intact. Four core features in the gender norms discourse include:

- Gender norms are learned in childhood, from parents and peers, in a process known as socialisation and then reinforced or contested in the larger social context.

- Inequitable gender norms reflect and perpetuate inequitable power relations that are often disadvantageous to women.

- Gender norms are embedded in and reproduced through institutions.

- Gender norms are produced and reproduced through social interaction.

The article examines six key differences between social and gender norms, which are related to:

- The type of construct traditionally associated with gender vs. social norms - Gender norms are in the world, embedded in institutions and reproduced by people's actions, whereas social norms are in the mind: people's beliefs are shaped by their experiences of other people's actions and manifestations of approval and disapproval.

- The way in which these norms reproduce themselves over time - Gender norms are produced and reproduced through people's actions and enforced by powerholders who benefit from people's compliance with them, whereas social norms maintain themselves, not necessarily benefitting anyone.

- The relation between the norms and personal attitudes - Gender norms are often studied as shaping people's individual attitudes, whereas social norms are often studied as diverging from people's individual attitudes.

- The boundaries within which the norms apply - People follow the gender norms of their culture, society, or group, the boundaries of which are usually blurry, whereas people follow the social norms of their reference group, the boundaries of which are usually defined.

- The processes required for changing them - Changing gender norms requires changing institutions and power dynamics, often through conflict and renegotiation of the power equilibrium, whereas changing social norms (at its simplest) requires changing people's misperceptions of what others do and approve of in their reference group.

- The larger project that animates each tradition - Changing gender norms is a social movement that aims to change the status quo and the power relations embedded in it, whereas changing social norms is a health-related project that aims for greater well-being for women and men.

Taking these features into account, the researchers propose a definition of gender norms that takes into account both intellectual traditions. "A starting point might be agreeing on the fact that many social norms are gender norms. People do not simply hold beliefs about what is expected from them, they hold beliefs about what is expected from them because of their sex and socially constructed rules of behaviour assigned to that sex." Specifically, they put forth this definition: "Gender norms are social norms defining acceptable and appropriate actions for women and men in a given group or society. They are embedded in formal and informal institutions, nested in the mind, and produced and reproduced through social interaction. They play a role in shaping women and men's (often unequal) access to resources and freedoms, thus affecting their voice, power and sense of self."

It is the hope that the increased clarity afforded by this definition and broader analysis will improve efforts to address harmful norms and practices.

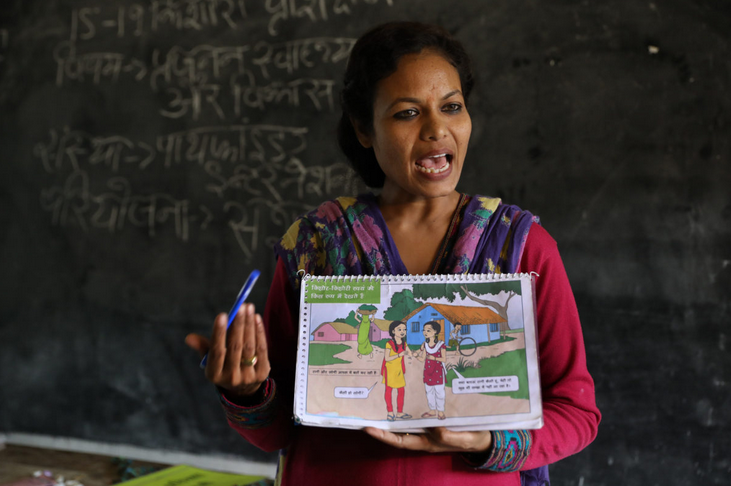

Sociology of Health & Illness Vol. 42 No. 2 2020 ISSN 0141-9889, pp. 407-22 doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13008. Image credit: Paula Bronstein/Getty Images/Images of Empowerment - Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

- Log in to post comments